Ring Buffer Series Part 1 - Classes and Functions - The Building Blocks

Hello! If you recall from the previous series, we built a program that handled text input, stored numbers into a vector and performed calculations. However there were some concepts in there that we used, but that I didn’t really explain. I am referring to iterators. In this new series I aim to go over what they are, how they work and how to use them, so get ready because it will be a bumpy ride and as usual, we will have to build our way there because fundamentals are always important.

Hello! If you recall from the previous series, we built a program that handled text input, stored numbers into a vector and performed calculations. However there were some concepts in there that we used, but that I didn’t really explain. I am referring to iterators. In this new series I aim to go over what they are, how they work and how to use them, so get ready because it will be a bumpy ride and as usual, we will have to build our way there because fundamentals are always important.

The Project:

Implement a fixed-size Ring buffer (ring_buffer<T, N>) with complete iterator support. This is a genuinely useful data structure while being perfect for teaching iterator fundamentals.

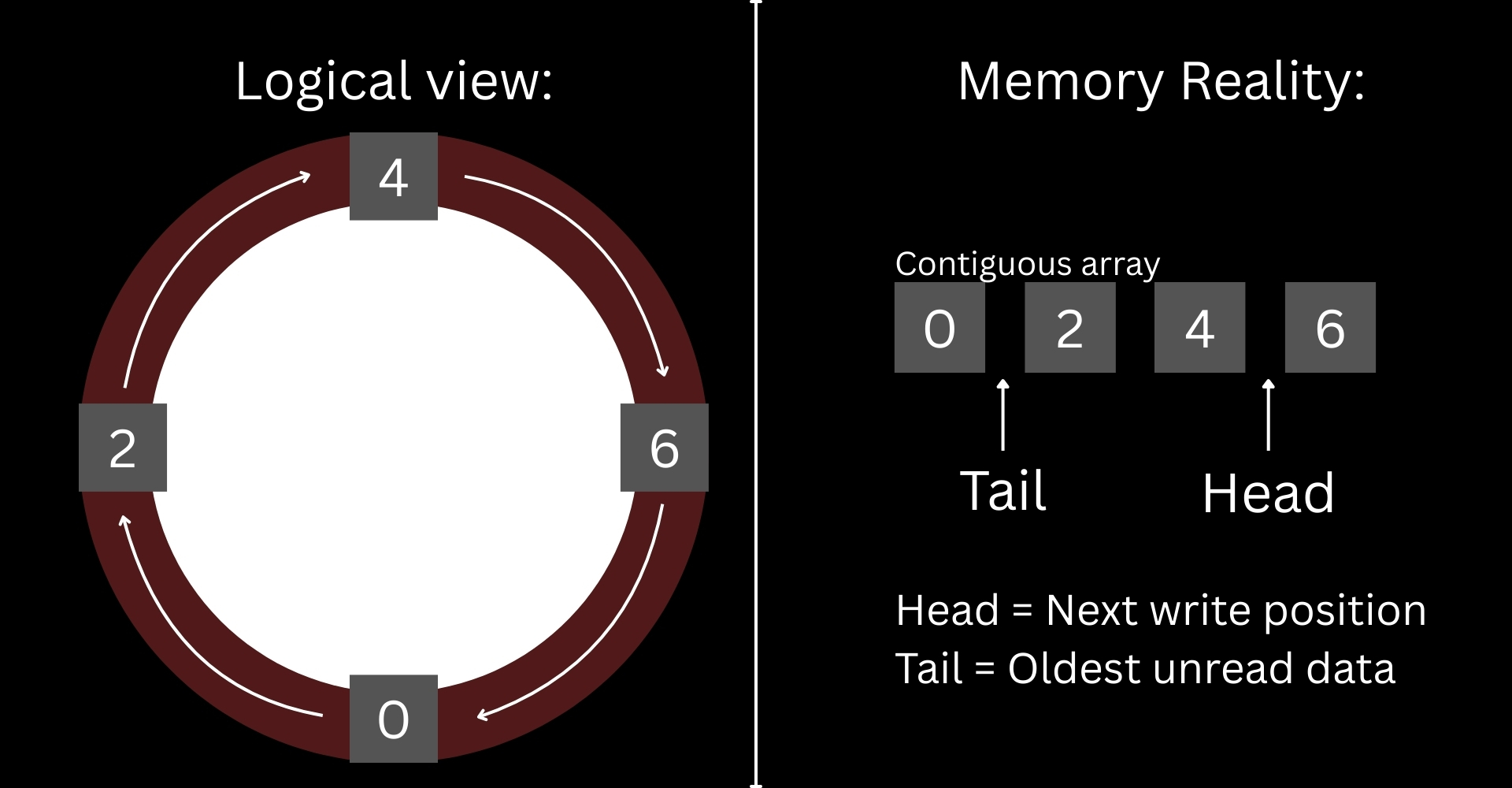

What is a Ring Buffer?

A ring buffer (also called circular buffer) is a fixed-size data structure that overwrites its oldest elements when full. Imagine a Ring track where a writer chases a reader. When the writer catches up, the oldest data gets overwritten.

This is a useful container type, popular in logging systems, audio/video streaming and other fields. A ring buffer is used when the only thing you care about is recent data and you have memory constraints.

The Beginning

If you recall from the Input Basics series, we started by including existing libraries into our project, so that we didn’t have to start from scratch, however there are situations where the standard library does not have a type that we can include and use it from the get go, and this is one of those situations. The standard library doesn’t include a ring buffer type, this means we will have to create our own and to do that, we will have to create a class.

What is a class?

A class is a user-defined type. Think of it as a blueprint to create something, these things that are created from the class are called instances. In short, you can define a class as a type of thing. Classes are used to group related components, like variables, called data members and functions that perform operations related to the class.

Hold it right there! What is a function?

A function is a construct in C++ that allows us to put code snippets under a name. Functions allow us to break complex tasks into more manageable steps. Functions allow us to write reusable code, so we don’t have to write the same logic over and over.

#include <iostream>

int multiply(int a, int b)

{

return a * b;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << "Multiplying 2 by 6\n";

int result{multiply(2, 6)};

std::cout << "The result is: " << result << '\n';

std::cout << "Multiplying 4 by 5\n";

int result2{multiply(4, 5)};

std::cout << "The result is: " << result2 << '\n';

return 0;

}

As you can see, in the code above I am using the multiply function to assign the product of two values to result and result2, if I didn’t use the function, then every time I needed to multiply two values I would have to write the actual operation over and over again.

This is a simple example, but there will be more complex code that you wouldn’t want to have to write over and over.

Return Type

Maybe you noticed that int before the function name. This is called a return type and it specifies if and what kind of data type the function will return after it has finished doing its thing. In this example, multiply() returns an integer type that is printed to the screen. A function can return anything, but sometimes there are cases where we need to make something happen, but don’t need a return, for these cases, then we specify void as the return type.

Parameters/Arguments

You also noticed that inside the parentheses of the function I also have some variables multiply(int a, int b). Those are called parameters, which are variables the function will use during its lifetime, these parameters are placeholders for the actual values that will be used when calling the function, for example multiply(4, 5). In here, a and b are replaced by 4 and 5, so the function multiplies 4x5 and returns 20.

Back to classes

As I mentioned, a class is a user-defined type that contains member variables and member functions. We create classes, so that we can create instances of the objects we intend to use during our program execution. One way to see it, a class is a custom lego piece that you create using basic lego pieces. For example:

class Person

{

public:

Person() = default;

~Person() = default;

void PrintFullName();

private:

std::string name{"John"};

std::string lastname{"Doe"};

};

In this example, we are using two std::string types to help us create a Person class type. Notice the public and private sections, these are called access modifiers. An access modifier is something that allows or prevents others to access the members of a class. For example:

int main()

{

Person person_instance;

person_instance.PrintFullName();

return 0;

}

In this code, I am creating an instance of Person and I am calling it person_instance. Then the next thing that I am doing is “asking” person_instance to print its name to the screen by calling the function PrintFullName(). Now consider the following:

int main()

{

Person person_instance;

std::cout << person_instance.name << ' ' << person_instance.lastname << '\n';

return 0;

}

If I tried to run this code the compiler would give me an error because both name and lastname are inaccessible to anyone outside the Person class. Now, you may have noticed that PrintFullName() does not look like the multiply() that I created at the beginning and you may be wondering what the execution looks like, this is because in C++ we can declare a function and then we can create its definition. In the Person class, the PrintFullName() is declared, but at the moment it is not defined and if we try to run the program, we will get an error saying the definition for the function is missing, basically this means that the compiler wouldn’t know what to do once it needs to execute that function, so I need to provide a definition for the function, so that the program can execute it.

When it comes to member functions, there are two ways to define them.

Header vs Implementation Files

While we can code our entire program in an entire file, history has proven that sometimes it is better to divide and conquer. When a program becomes too large and difficult to maintain and manage, we break it down into smaller chunks. Now, this is not done for the computers, computers will process almost anything you throw at them, we divide and organize files for us, human readers, so that we can extend, change and debug easily. I mentioned that there are two ways to define member functions. The first one is within the class itself.

class Person

{

public:

Person() = default;

~Person() = default;

//Member function defined inside the class

void PrintFullName()

{

std::cout << name << " " << lastname << '\n';

}

private:

std::string name{"John"};

std::string lastname{"Doe"};

};

And the second one can be done outside of the class as follows:

class Person

{

public:

Person() = default;

~Person() = default;

void PrintFullName();

private:

std::string name{"John"};

std::string lastname{"Doe"};

};

//Member function defined outside of the class.

void Person::PrintFullName()

{

std::cout << name << ' ' << lastname << '\n';

}

At first glance, this is just more work for less, but there is a reason for this. What happens is that if you put declarations and definitions in the same place, any tiny change that you make to the file will result on a recompilation of the entire thing, even if the change was as small as adding a semicolon. As of right now, even though the function is defined outside the class, it still lives in the same file, so in this case defining the function inside or outside the class doesn’t really make a difference, however, what happens if we were to move the function definition to a different file? This is where header and implementation files come up.

A header file (.h/.hpp) specifies the interface of a component, in this case it would be the Person class interface. The interface tells the compiler about what a class can do, but not how it does it. The implementation file (.cpp) is where the function definition, the code and operations reside. Here is the updated example.

Person.h

#ifndef PERSON_H

#define PERSON_H

#include <string>

class Person

{

public:

Person() = default;

~Person() = default;

void PrintFullName();

private:

std::string name{"John"};

std::string lastname{"Doe"};

};

#endif

Person.cpp

#include "Person.h"

#include <iostream>

void Person::PrintFullName()

{

std::cout << name << ' ' << lastname << '\n';

}

This also carries other benefits such as increased compilation speed, now if I make a change in PrintFullName(), only Person.cpp will have to be compiled while Person.h will not and many other advantages that I will discuss in future articles.

Constructors and Destructors

You may have noticed these two lines in the Person class

Person() = default;

~Person() = default;

These are special member functions that every class has.

A constructor Person() is a function that runs automatically when an instance is created. Its job is to set up the object and ensure it starts in a valid state. The constructor has the same name as the class and has no return type, not even void.

A destructor ~Person() is a function that runs automatically when an instance is destroyed (goes out of scope or is deleted). Its job is to clean up any resources the object was using. The destructor has the same name as the class it belongs to, only that we add the ~ symbol at the beginning.

The =default syntax tells the compiler to generate a standard version of the constructor and destructor, this is useful when we only want default behaviour, if we needed something special to happen, then we would write code in the constructor definition, like in any other function. As of right now, the defaults are just fine for what we are doing, but later on we will encounter cases where we need to define constructors and destructors.

Where We Are Headed

Phew, that was quite a lot for an introductory post, but I think it gives us what we need to move to the next step. By the end of this series, we will have a ring buffer that supports range-based loops and works with STL algorithms. Here is a preview!

RingBuffer buffer;

buffer.push_back(10);

buffer.push_back(20);

for (int value : buffer){

std::cout << value << '\n';

}