Ring Buffer Series Part 2 - Implementation

In Part 1 we covered the fundamental building blocks: classes, functions, constructors and how to organize code into header and implementation files. We created a simple

In Part 1 we covered the fundamental building blocks: classes, functions, constructors and how to organize code into header and implementation files. We created a simple Person class to illustrate these concepts and now it is time to apply what we learned to our main project: The RingBuffer.

Remember, our ring buffer needs to do a few key things: store elements, track where to add the next one, and know when it’s full. Let’s begin by creating a class.

#ifndef RINGBUFFER_H

#define RINGBUFFER_H

class RingBuffer

{

public:

RingBuffer(); //Constructor

~RingBuffer(); //Destructor

void print_buffer() const; //Outputs the buffers contents to the screen

void push_back(unsigned int new_element); //Adds a new element into the buffer

void pop_front(); //Deletes the oldest element from the buffer

bool empty() const; //Is the buffer empty

bool full() const; //Is the buffer full

unsigned int front() const; //Retrieves the oldest element

unsigned int size() const; //Retrieves the number of elements in the buffer

private:

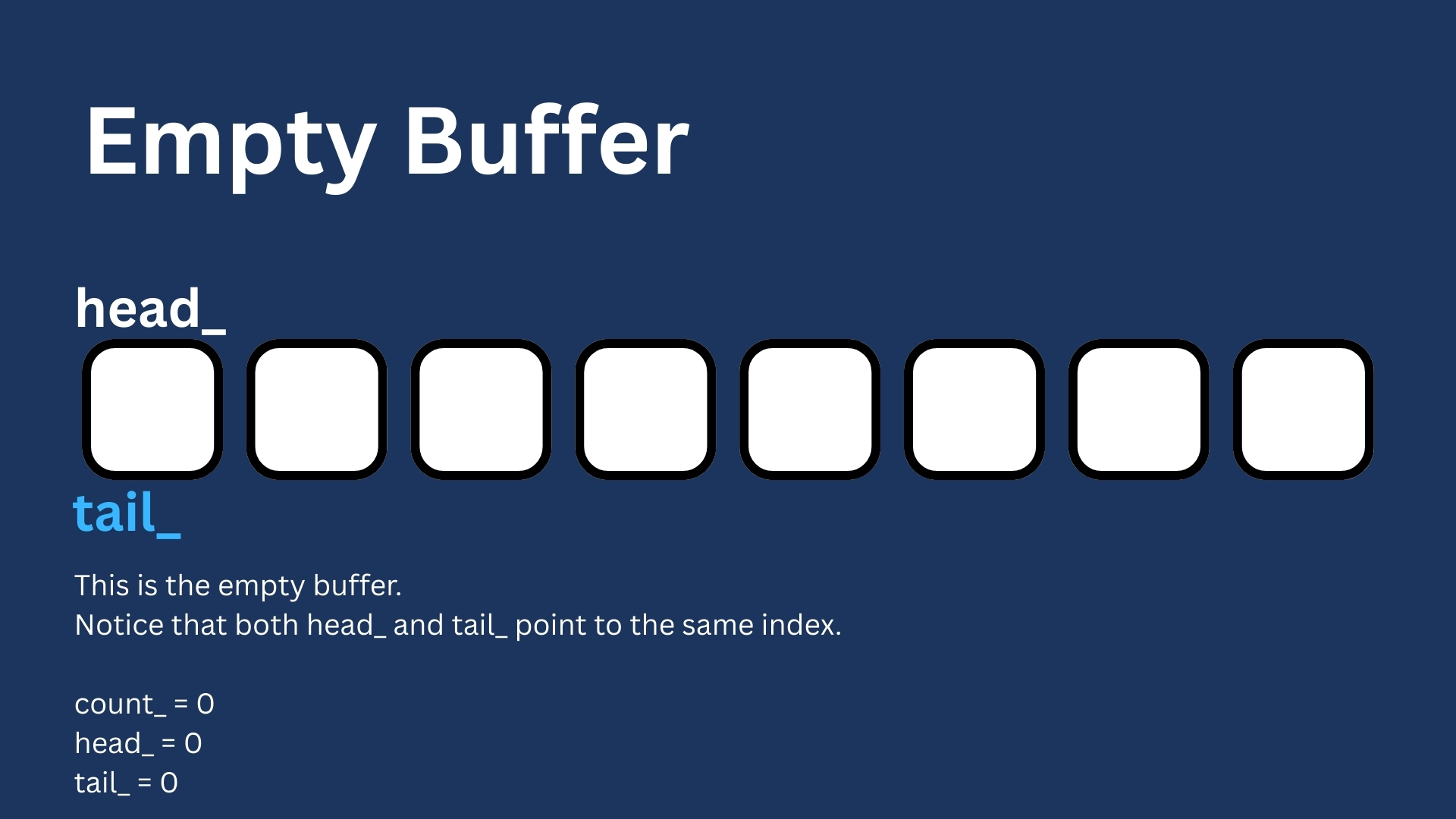

unsigned int buffer_[8]; //The actual buffer container, in this case an array.

unsigned int head_; //Index of oldest element (read position)

unsigned int tail_; //Index of next write position

unsigned int count_; //Total number of elements in the buffer

};

#endif // RINGBUFFER_H

Perhaps you are wondering what these #ifndef, #define, #endif are. To answer that there are a few things we need to talk about first.

Preprocessor Directives

A preprocessor directive is a special instruction that run as a separate step before compilation. Preprocessor directives are a “find-and-replace” tool that makes changes to the source code before it is compiled. For example #include <vector> tells the preprocessor to take the contents of a file called vector and paste them into the current file. What I am using in the RingBuffer example is a different set of preprocessor directives known as compiler guards, header guards or include guards.

Compiler Guards

The combination of #ifndef, #define, #endif prevent the preprocessor from copying a file more than once, which happens a lot in larger projects. if we don’t use compiler guards, then a header file could be copied more than once creating code duplication errors. Note that compiler guards are commonly placed in header files.

Defining the Buffer Methods

Constructor

RingBuffer::RingBuffer(): buffer_{}, head_{}, tail_{}, count_{} {

}

Notice that I have put the variables to the right of the constructor along with {}. This is called a constructor initialization list and in C++ we do things this way for a couple reasons.

In C++ when execution reaches a class contructor’s body, the class members have already been created if we were to initialize the values in the old fashion way as follows:

RingBuffer::RingBuffer() {

head_ = 0;

tail_ = 0;

count_ = 0;

}

However in C++, is known as constructor assignment, so essentially what happens is that the program will create the member variables of RingBuffer and then will construct-assign them. In smaller programs, this is fine, but when we are talking about real world programs, this could have a significant performance impact. When variables are instead contruct-initialized, then the compiler can initialize member variables at creation time, meaning that the assignment step is no longer needed.

push_back(unsigned int new_element)

void RingBuffer::push_back(unsigned int new_element)

{

if(count_ == 8){

// Buffer full, advance head_ to abandon oldest element

head_++;

if(head_ >= 8){

head_ = 0;

}

}else{

count_++;

}

buffer_[tail_] = new_element;

tail_++;

if(tail_ >= 8){

tail_ = 0;

}

}

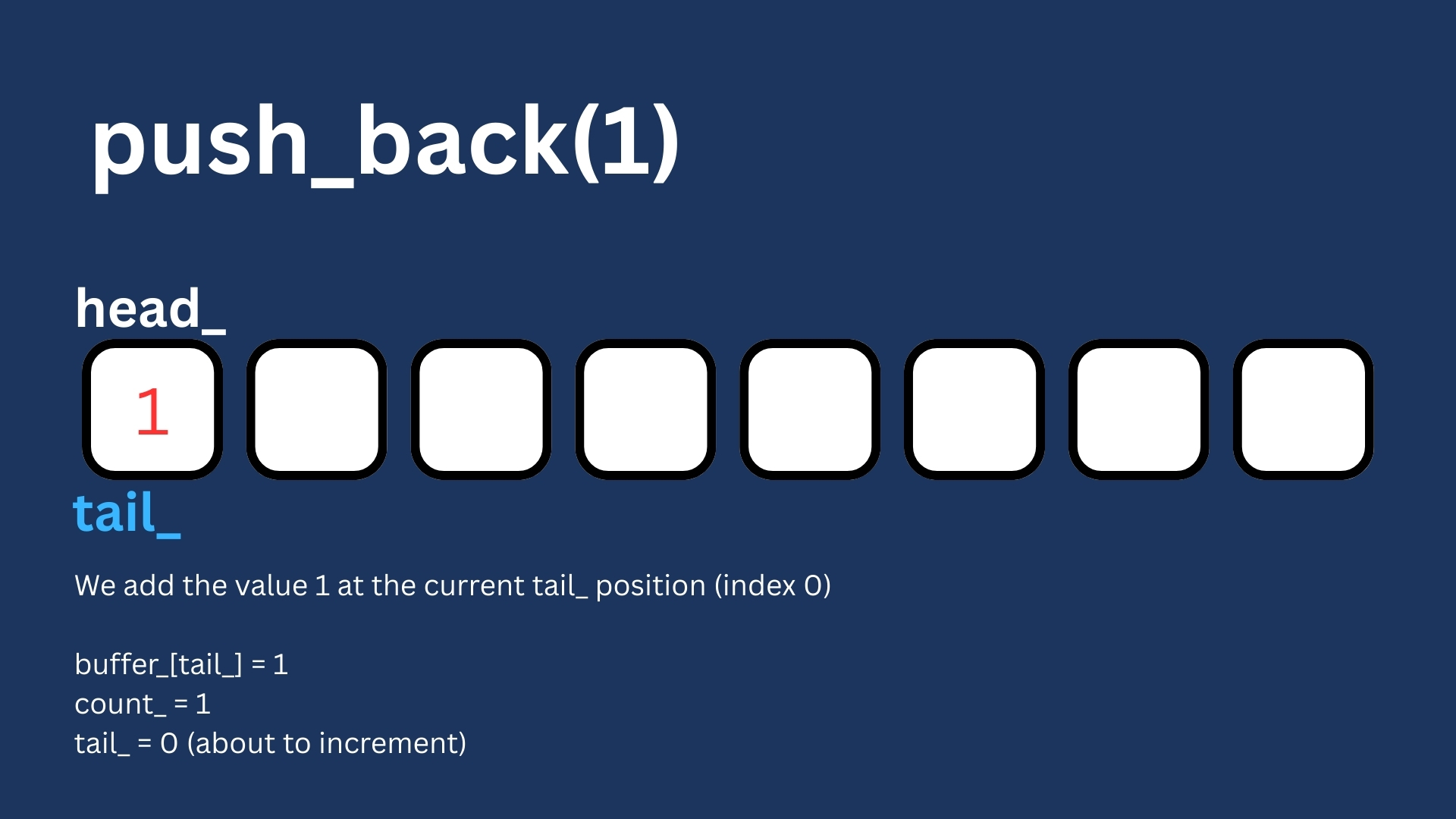

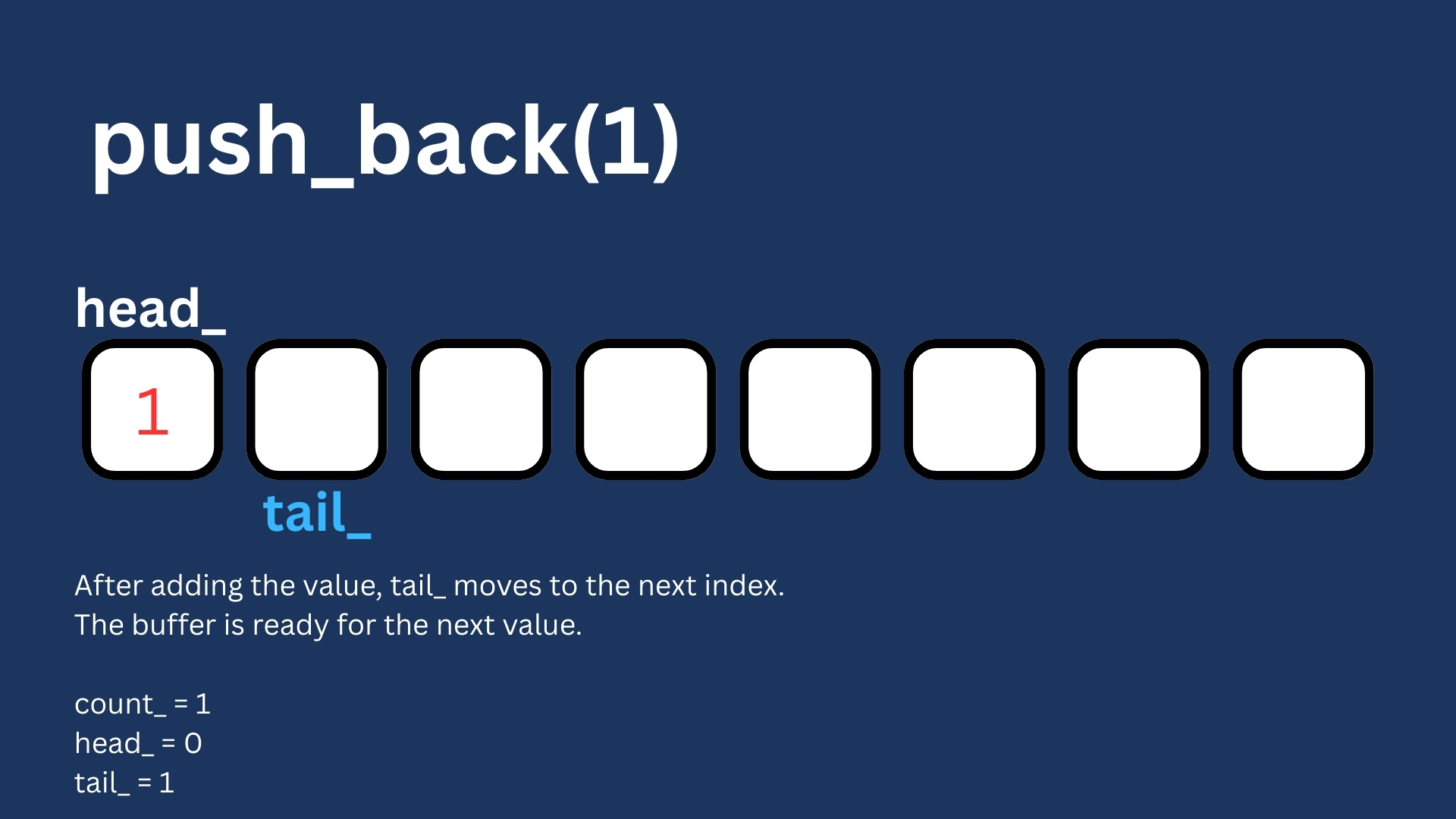

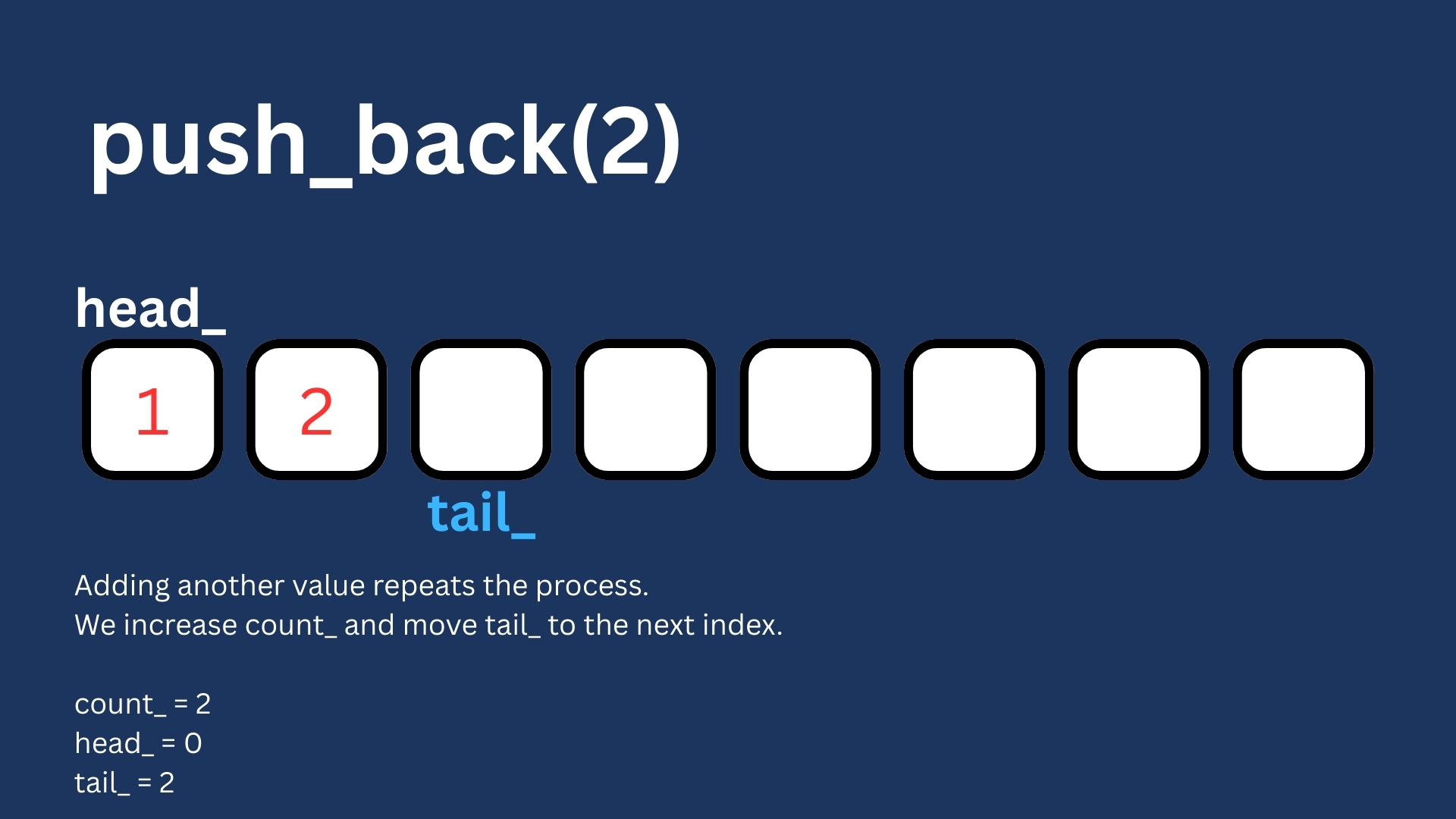

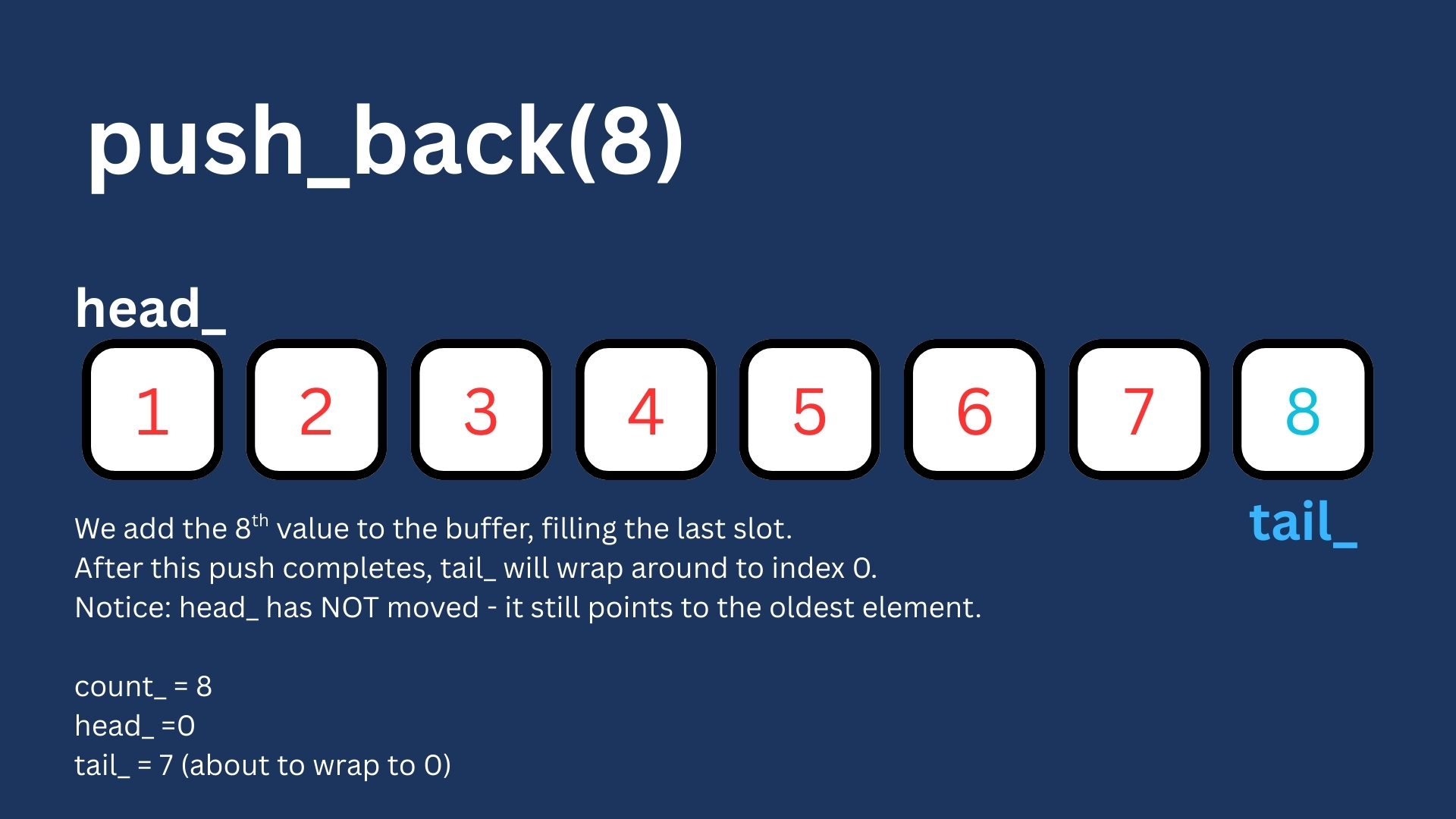

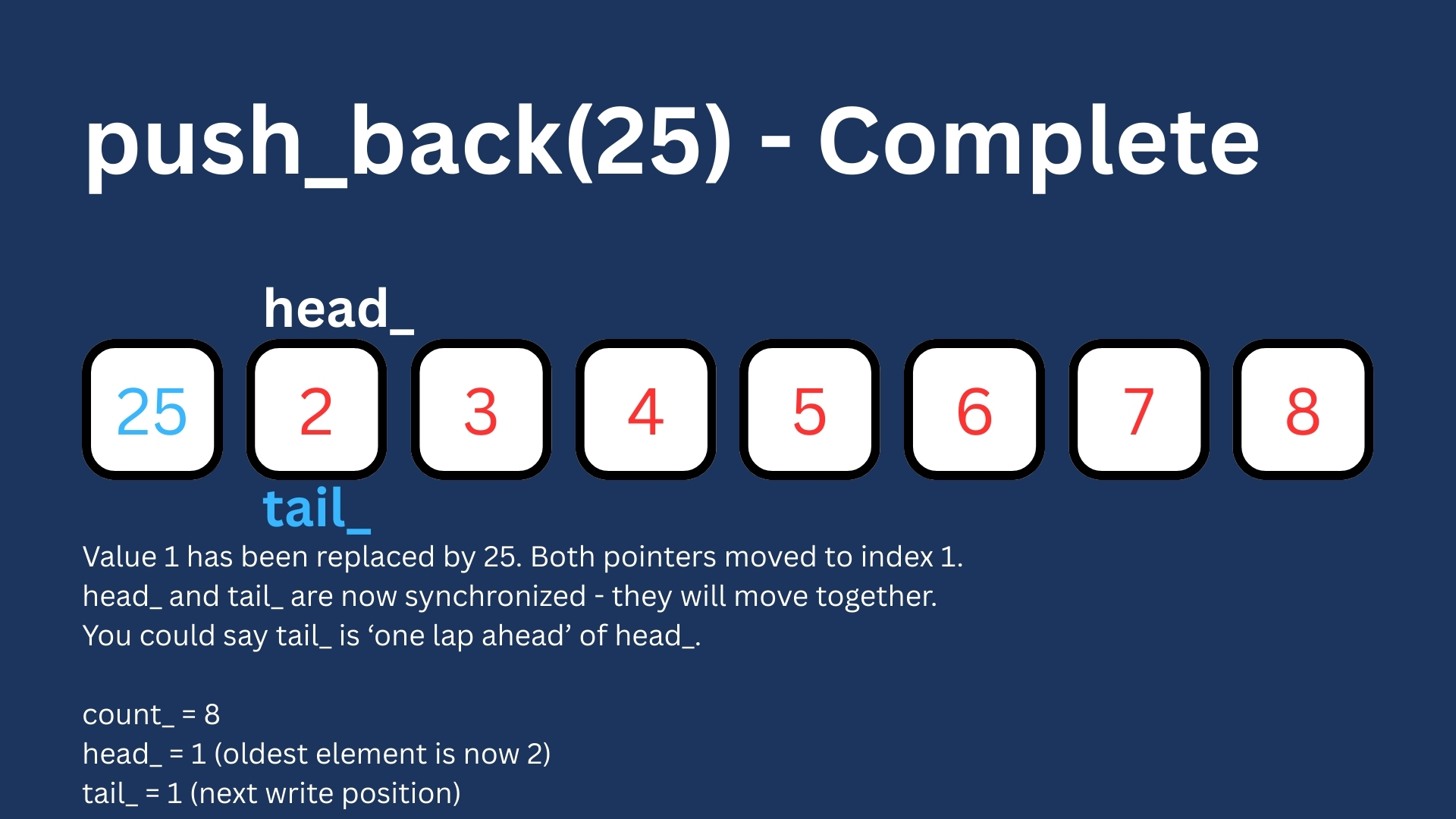

When adding a new element to the buffer it is important to always ask two questions: Where do we write, and is the buffer full?.

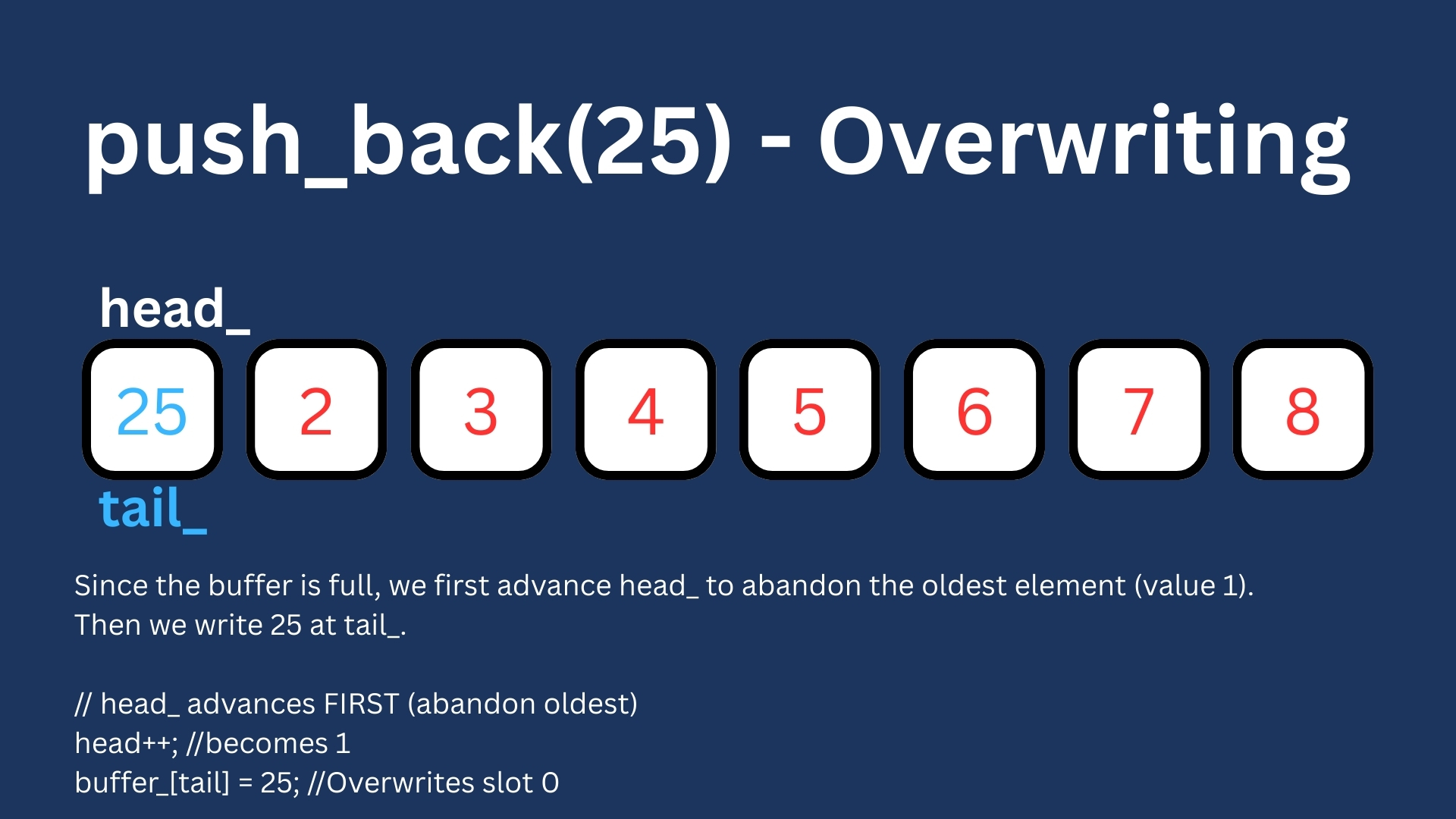

We always write at tail. That’s the next available slot, but before writing, we check if the buffer is already full.

If it is full, then we have to overwrite the oldest element and to do that we need to advance head_ first, if we don’t then head would point to a slot that contains the newest element, breaking our ability to read in the correct order.

After writing, tail_ advances to the next slot. When it reaches 8 (last index), it wraps back to 0. This is why it is called a ring or a circular buffer.

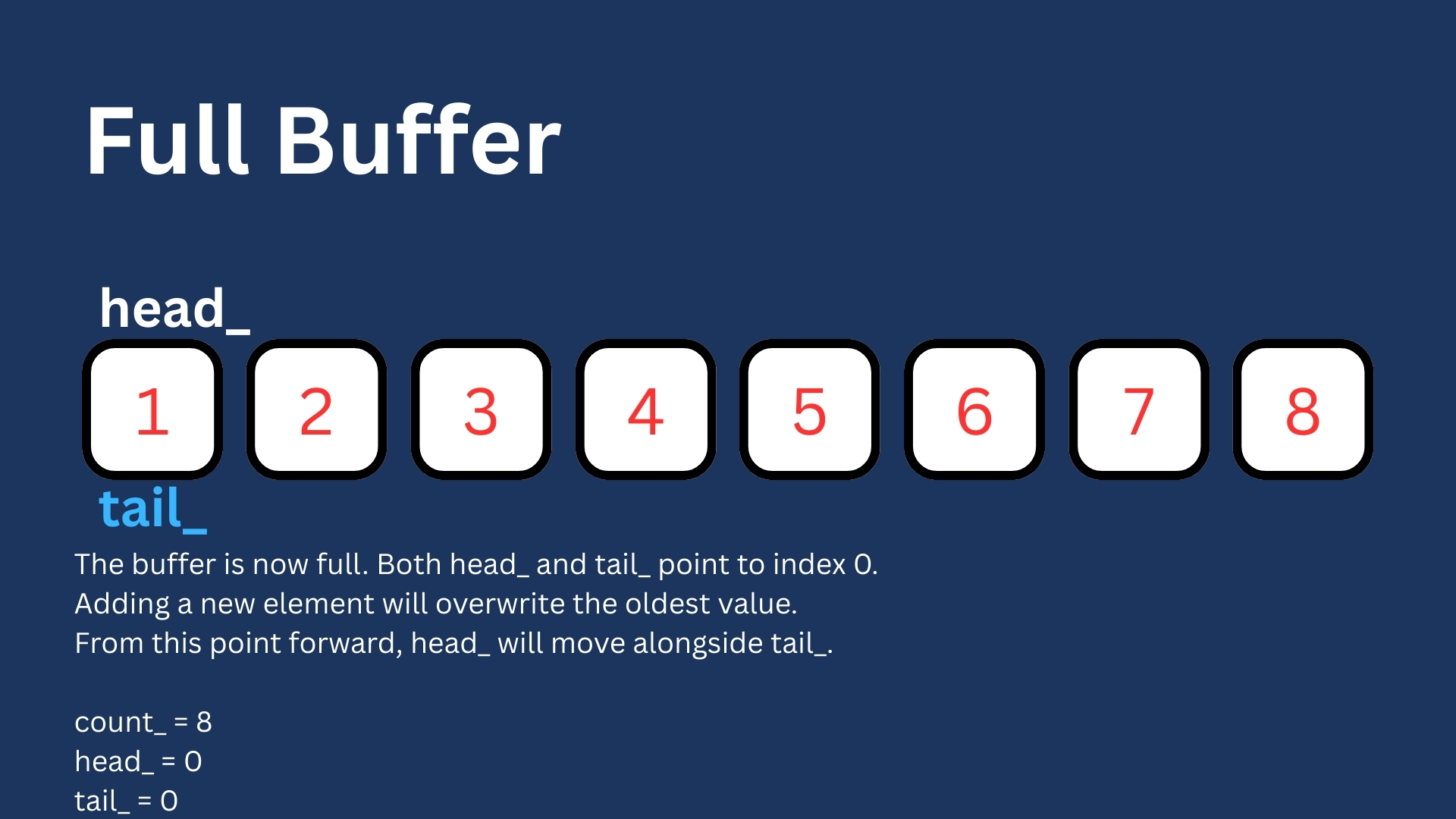

What if the buffer becomes full?

Once count_ reaches 8, every new push overwrites the oldest value. Now head_ and tail_ move together like two runners on a track, with tail_ always one lap ahead.

pop_front()

void RingBuffer::pop_front()

{

if(count_ == 0){

// Buffer empty, nothing to remove

return;

}

head_++;

if(head_ >= 8){

head_ = 0;

}

count_--;

}

Removing an element from the buffer is simpler. All we need to do is advance head_ to the next index.

Notice that we don’t actually delete anything from the buffer. The value stays in the array. We just move head_ and decrement count_. That slot is now considered empty for all intents and purposes and will eventually be overwritten by a future push_back().

print_buffer()

void RingBuffer::print_buffer() const

{

unsigned int index{head_};

for(unsigned int i = 0; i < count_; i++){

std::cout << buffer_[index] << ' ';

index++;

if(index >= 8){

index = 0;

}

}

std::cout << '\n';

}

This function prints only the valid elements in the buffer, from oldest to newest. If the buffer is empty, nothing is printed.

bool RingBuffer::empty()

bool RingBuffer::empty() const

{

return count_ == 0;

}

This function will check if count_ is zero, if it is, then that means the buffer is empty.

bool RingBuffer::full()

bool RingBuffer::full() const

{

return count_ == 8;

}

This function will check if count_ is 8, if it is, then that means the buffer is full.

unsigned int RingBuffer::size()

unsigned int RingBuffer::size() const

{

return count_;

}

This function will return the number of elements stored in the buffer.

unsigned int RingBuffer::front()

unsigned int RingBuffer::front() const

{

assert(!empty());

return buffer_[head_];

}

This function will return the oldest element in the buffer.

Putting Everything Together

The following is what RingBuffer.cpp will end up looking like.

#include "ringbuffer.h"

#include <iostream>

#include <cassert>

RingBuffer::RingBuffer(): buffer_{}, head_{}, tail_{}, count_{} {

}

RingBuffer::~RingBuffer(){}

void RingBuffer::print_buffer() const

{

unsigned int index{head_};

for(unsigned int i = 0; i < count_; i++){

std::cout << buffer_[index] << ' ';

index++;

if(index >= 8){

index = 0;

}

}

std::cout << '\n';

}

void RingBuffer::push_back(unsigned int new_element)

{

if(count_ == 8){

//Buffer full - We are about to overwrite oldest element

head_++;

if(head_ >= 8){

head_ = 0;

}

}else{

count_++;

}

buffer_[tail_] = new_element;

tail_++;

if(tail_ >= 8){

tail_ = 0;

}

}

void RingBuffer::pop_front()

{

if(count_ == 0){

// Buffer empty, nothing to remove

return;

}

head_++;

if(head_ >= 8){

head_ = 0;

}

count_--;

}

bool RingBuffer::empty() const

{

return count_ == 0;

}

bool RingBuffer::full() const

{

return count_ == 8;

}

unsigned int RingBuffer::front() const

{

assert(!empty());

return buffer_[head_];

}

unsigned int RingBuffer::size() const

{

return count_;

}

Seeing it in action:

Now that we have this RingBuffer class defined, let us take it for a test drive.

#include "ringbuffer.h"

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

RingBuffer buffer_{};

buffer_.push_back(0);

buffer_.print_buffer();

std::cout << std::boolalpha; //Enable printing "true"/"false"

std::cout << "Buffer size: " << buffer_.size() << '\n';

buffer_.push_back(1);

buffer_.print_buffer();

std::cout << "Buffer size: " << buffer_.size() << '\n';

buffer_.push_back(2);

buffer_.print_buffer();

std::cout << "Buffer size: " << buffer_.size() << '\n';

buffer_.push_back(3);

buffer_.print_buffer();

std::cout << "Buffer size: " << buffer_.size() << '\n';

buffer_.push_back(4);

buffer_.print_buffer();

std::cout << "Buffer size: " << buffer_.size() << '\n';

buffer_.push_back(5);

buffer_.print_buffer();

std::cout << "Buffer size: " << buffer_.size() << '\n';

buffer_.push_back(6);

buffer_.print_buffer();

std::cout << "Buffer size: " << buffer_.size() << '\n';

buffer_.push_back(7);

buffer_.print_buffer();

std::cout << "Buffer size: " << buffer_.size() << '\n';

buffer_.push_back(8);

buffer_.print_buffer();

std::cout << "Buffer size: " << buffer_.size() << '\n';

buffer_.push_back(9);

buffer_.print_buffer();

std::cout << "Buffer size: " << buffer_.size() << '\n';

std::cout << "Buffer is full: " << buffer_.full() << '\n';

buffer_.pop_front();

buffer_.print_buffer();

std::cout << "Buffer size: " << buffer_.size() << '\n';

std::cout << "Buffer is empty: " << buffer_.empty() << '\n';

std::cout << "Buffer is full: " << buffer_.full() << '\n';

std::cout << "Oldest element in buffer: " << buffer_.front() << '\n';

}

When running this code, the output is as follows:

0

Buffer size: 1

0 1

Buffer size: 2

0 1 2

Buffer size: 3

0 1 2 3

Buffer size: 4

0 1 2 3 4

Buffer size: 5

0 1 2 3 4 5

Buffer size: 6

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

Buffer size: 7

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Buffer size: 8

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Buffer size: 8

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Buffer size: 8

Buffer is full: true

3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Buffer size: 7

Buffer is empty: false

Buffer is full: false

Oldest element in buffer: 3

Next Steps

In the next chapter, we’ll make the buffer work with any data type using templates and give it a dynamic size. After that, we’ll tackle iterators, the mechanism that will let our RingBuffer work with range-based for loops and STL algorithms.