Input Basics In C++ Part 2 - Streams, Flags and Validation

In Part 1 of this series I covered some C++ fundamentals by building a small unit converter. While the program worked, it had a critical weakness: it assumed the “happy path,” where users never make mistakes. In the real world, things are messy, and as programmers, we have to anticipate how our applications might fail. We can’t predict everything, but we can certainly guard against the most common issues.

In today’s post, we’ll build a different program to illustrate some more robust techniques. Then, we’ll circle back and apply these new concepts to our original unit converter.

The Project.

We’re going to build a mean calculator. This program will let a user enter as many numbers as they want. Once they’re done, it will calculate the mean, maximum, and minimum values and display the results. If the user enters something that isn’t a number (like a letter or symbol), the program will display a friendly error and ask them to try again.

Understanding the Problem.

Like with our unit converter, let’s start by breaking down the problem. The core requirement is handling a series of numbers from the user. They can enter as many values as they like. This tells us we need a place to store these numbers as they come in. A simple variable won’t do; we need a container. In C++, the go-to choice for this is the std::vector.

What is a Vector?

Often called the container of choice in C++, you can think of a std::vector as a dynamic, ordered row of storage boxes.

A vector lets you add new boxes, remove old ones, and find a specific box in the row. For our program, every time the user enters a number, we’ll add a new ‘box’ to our vector to store it. There’s a lot more to std::vector, but since this post focuses on input, a deep dive into containers will have to wait.

Under the Hood: A vector stores elements in contiguous memory (like an array), but automatically resizes when it runs out of space. This makes it cache-friendly and fast for sequential access—topics we’ll explore when discussing performance.

For now, all we need to do is include the header:

#include <vector>

Of course, just like with iostream, including the header isn’t enough. We also need to create a std::vector variable for our program to use.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

//This function is the entry point of the application.

int main()

{

std::vector<double> numbers{};

return 0;

}

With this, we now have a program that creates an empty vector of floating-point numbers (decimals) and then immediately exits. It ain’t much, but it’s honest work!

User Input

Another requirement is for the program to accept input continuously until the user signals they’re finished. This calls for our trusty input and output functionality, similar to what we used in Part 1. After modifying the program, it looks like this.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

//This function is the entry point of the application.

int main()

{

std::cout << "Welcome to the mean calculator program, please enter your name: ";

std::string username{};

std::cin >> username;

std::cout << username << ", please enter the numbers you want to calculate the mean for.\n";

std::vector<double> numbers{};

return 0;

}

The program now asks for the user’s name and prints it back to the screen. But we’ve already introduced a subtle bug. What happens if someone enters their first and last name?

As you can see, even though the user entered a first and last name, only the first name was printed. This behavior is due to how std::cin interacts with input streams and buffers.

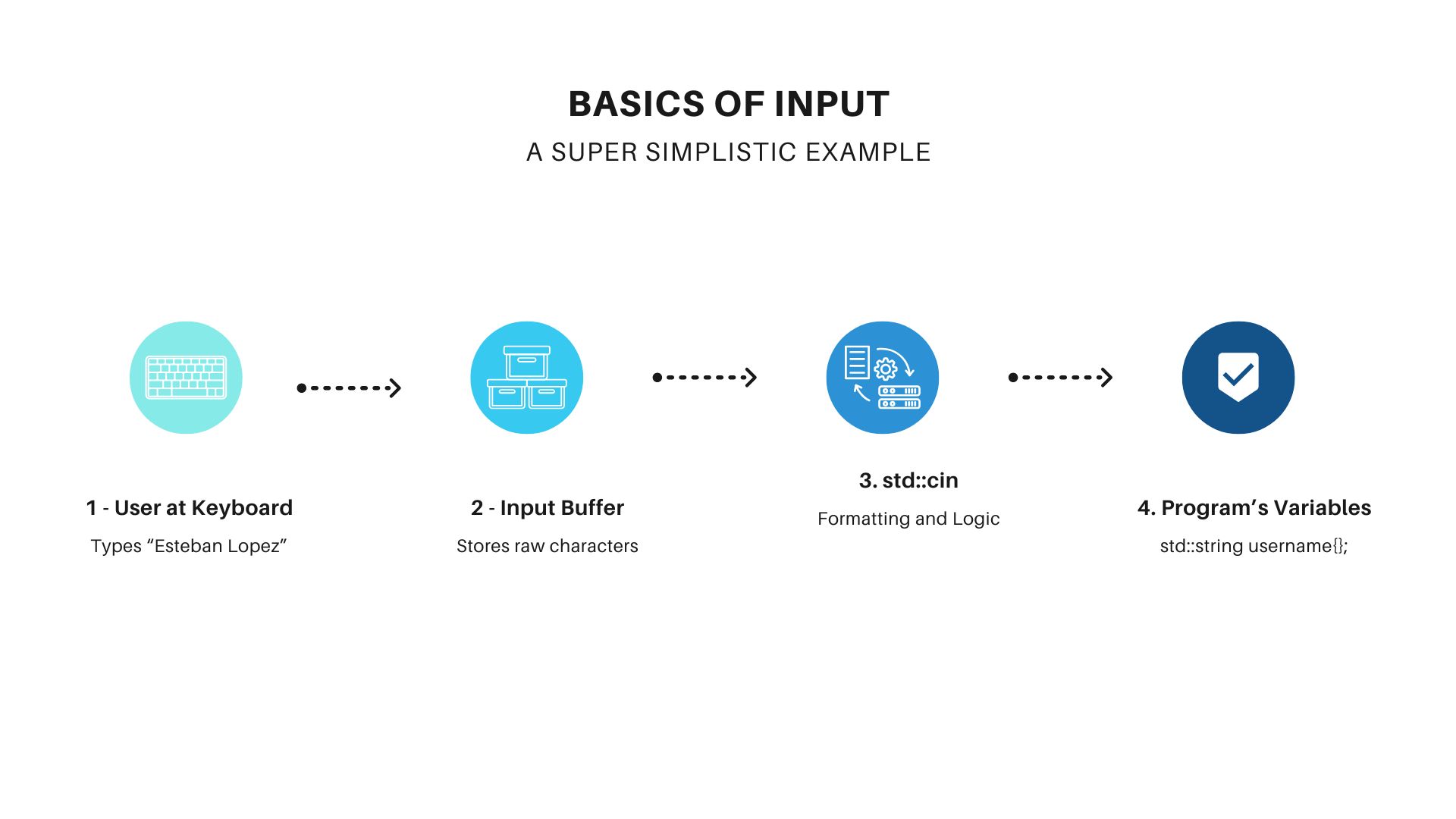

Streams, Buffers, std::cin and why you should care.

When you use std::cin, a sequence of events unfolds behind the scenes. First, the user types data on the keyboard. This data doesn’t go directly to your variable (username in this case). Instead, it lands in a temporary memory area called an input buffer. From there, std::cin extracts the characters and places them into their destination.

The analogy of a warehouse works well here: the user typing is like a truck delivering boxes. The input buffer is the warehouse receiving dock. std::cin is the worker who takes the boxes from the dock and puts them on the correct shelf.

In our example, when the user types “Esteban Lopez” and hits Enter, the entire string, including the space, goes into the input buffer. However, by default, std::cin stops reading as soon as it encounters the first whitespace character. It reads “Esteban”, places it in the username variable, and leaves " Lopez" sitting in the buffer. This leftover data can cause unexpected problems, as we’ll see next.

Let’s add a bit more to our program to see the consequences.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

// This function is the entry point of the application.

int main() {

std::cout << "Welcome to the mean calculator program, please enter your name: ";

std::string username{};

std::cin >> username;

std::cout << username << ", please enter the numbers you want to calculate the mean for.\n";

std::vector<double> numbers{};

double number{};

std::cout << username << " please enter a number to be stored: ";

std::cin >> number;

std::cout << username << ", the number you entered was: " << number;

return 0;

}

Now we are asking the user for a single number, but watch what happens when we run it with a full name:

The program doesn’t even wait for us to enter a number! That’s because when std::cin >> number executes, it sees that " Lopez" is still in the input buffer. It tries to store that string in our double variable, which fails. Because we initialized number with double number{};, it starts at zero and the failed extraction leaves it unchanged. The program continues and prints zero.

Why Brace-Initialization Matters: Using double number{} guarantees zero-initialization. Without the braces (double number), an uninitialized variable contains garbage. When input fails, this garbage would be printed. A subtle but critical bug.

Taking Care of the Buffer

We have a few ways to solve this. One common approach is to clear the leftover data from the buffer before we ask for the next input. We can do this with a handy function: std::cin.ignore(). By default, ignore() discards only a single character. To clear the entire buffer, we need to tell it to ignore a very large number of characters.

std::cin.ignore(std::numeric_limits<std::streamsize>::max(), '\n');

Here is the updated program.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <limits>

// This function is the entry point of the application.

int main() {

std::cout << "Welcome to the mean calculator program, please enter your name: ";

std::string username{};

std::cin >> username;

std::cin.ignore(std::numeric_limits<std::streamsize>::max(), '\n');

std::cout << username << ", please enter the numbers you want to calculate the mean for.\n";

std::vector<double> numbers{};

double number{};

std::cout << username << " please enter a number to be stored: ";

std::cin >> number;

std::cout << username << ", the number you entered was: " << number;

return 0;

}

Getting in Line!

C++ provides more than one way to get user input. So far, we’ve used std::cin >>, which is great for simple data but struggles with whitespace. Fortunately, we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. The C++ Standard Library has a battle-tested solution: std::getline(). This function extracts all characters from the input stream until it hits a newline character.

std::string str{};

std::getline(std::cin, str);

By default, std::getline() extracts until it encounters \n (newline), which is then discarded. This is why we don’t need ignore() after getline. The newline is already consumed. Unlike operator>>, getline doesn’t skip leading whitespace.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

// This function is the entry point of the application.

int main() {

std::cout << "Welcome to the mean calculator program, please enter your name: ";

std::string username{};

std::getline(std::cin, username);

std::cout << username << ", please enter the numbers you want to calculate the mean for.\n";

std::vector<double> numbers{};

double number{};

std::cout << username << " please enter a number to be stored: ";

std::cin >> number;

std::cout << username << ", the number you entered was: " << number;

return 0;

}

And here is the result.

Success! Our program now correctly accepts a full name and then waits for us to enter a number. But what happens if the user enters text when a number is expected?

As you can see, when I enter “FortyTwo”, the input operation fails, and the number variable retains its default value of zero. According to our requirements, the program should detect this and ask the user to try again.

Input Validation… FINALLY!

To make something happen repeatedly in programming, we use a loop. For this task, we’ll use a while loop, which executes a block of code as long as a specified condition is true.

int i{0};

while(i < 5)

{

std::cout << "This is silly\n";

++i;

}

The code above will print “This is silly” five times. We can use this same concept to our advantage for input validation. The idea is simple: while the user input is invalid, display an error and ask for input again.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

// This function is the entry point of the application.

int main() {

std::cout << "Welcome to the mean calculator program, please enter your name: ";

std::string username{};

std::getline(std::cin, username);

std::cout << username << ", please enter the numbers you want to calculate the mean for.\n";

std::vector<double> numbers{};

std::cout << username << " please enter a number to be stored: ";

double number{};

while (!(std::cin >> number)) {

std::cout << username << ", the value you entered is not a number!\n";

}

std::cout << username << ", the number you entered was: " << number;

return 0;

}

The condition !(std::cin >> number) checks the state of the input stream. If the read operation is successful, it evaluates to true, and ! makes the condition false, so the loop doesn’t run. If the read fails, it evaluates to false, and ! makes the condition true, so the loop body executes.

Let’s see it in action.

Well, that was a bummer, wasn’t it? Why doesn’t this perfectly thought-out solution work? Should I just give up, pack my bags, and become a professional alpaca shearer? Let’s not be too hasty. The program is actually behaving exactly as it’s designed to. Let me explain.

The Four Stream State Flags

The standard input stream (std::cin) manages its state using a set of flags: goodbit, eofbit, failbit, and badbit. When an error occurs, the stream enters a ‘fail state’, and one of these flags is set. Once a flag is set, all future stream operations are ignored until we explicitly clear the error. These flags are collectively known as (cue Power Ranger music) the iostate.

goodbit

This flag indicates that everything is OK and that regular input operations can proceed as usual.

eofbit

This flag is set when the program tries to read past the end of a file.

failbit

This flag is set when an I/O operation fails, most commonly when you try to read data into an incompatible variable type—like trying to store “FortyTwo” in a double, which is exactly what’s happening in our program.

badbit

This flag signals a serious, often unrecoverable error, like data loss or a corrupted stream.

Clearing the Flags

We can clear eofbit and failbit using the std::cin.clear() function. This resets the stream’s state back to goodbit, allowing it to be used again. Let’s try it out.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

// This function is the entry point of the application.

int main() {

std::cout << "Welcome to the mean calculator program, please enter your name: ";

std::string username{};

std::getline(std::cin, username);

std::cout << username << ", please enter the numbers you want to calculate the mean for.\n";

std::vector<double> numbers{};

std::cout << username << " please enter a number to be stored: ";

double number{};

while (!(std::cin >> number)) {

std::cout << username << ", the value you entered is not a number!\n";

std::cin.clear();

}

std::cout << username << ", the number you entered was: " << number;

return 0;

}

To fix this, we need to not only clear the flags but also clear the buffer. It’s time to bring back our old friend, std::cin.ignore().

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <limits>

// This function is the entry point of the application.

int main() {

std::cout << "Welcome to the mean calculator program, please enter your name: ";

std::string username{};

std::getline(std::cin, username);

std::cout << username << ", please enter the numbers you want to calculate the mean for.\n";

std::vector<double> numbers{};

std::cout << username << " please enter a number to be stored: ";

double number{};

while (!(std::cin >> number)) {

std::cout << username << ", the value you entered is not a number!\n";

// 1. Clear the error flags

std::cin.clear();

// 2. Ignore the rest of the bad input

std::cin.ignore(std::numeric_limits<std::streamsize>::max(), '\n');

std::cout << "Please try again: ";

}

std::cout << username << ", the number you entered was: " << number;

return 0;

}

The combination of clear() and ignore() is the key. clear() resets the stream so it’s willing to work again, and ignore() discards the bad input that caused the problem in the first place.

Success! The program now validates input properly. With this milestone reached, we can finally start using that vector we declared.

Adding Elements to A Vector

Remember, a vector is a container for storing values of the same type for later use. For our program, we want to store every number the user enters so we can perform our calculations on the whole set. The standard way to add an element to the end of a vector is with the push_back() function.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

// This function is the entry point of the application.

int main() {

std::cout << "Welcome to the mean calculator program, please enter your name: ";

std::string username{};

std::getline(std::cin, username);

std::cout << username << ", please enter the numbers you want to calculate the mean for.\n";

std::vector<double> numbers{};

std::cout << username << " please enter a number to be stored: ";

double number{};

while (!(std::cin >> number)) {

std::cout << username << ", the value you entered is not a number!\n";

std::cin.clear();

std::cin.ignore(std::numeric_limits<std::streamsize>::max(), '\n');

std::cout << "Please try again: ";

}

numbers.push_back(number); //Insert a copy of number into the numbers vector.

std::cout << username << ", the number you entered was: " << number;

return 0;

}

But this approach has an obvious flaw: the program only accepts one number before it ends, which makes for a pretty useless calculator. We need a way to keep asking for numbers until the user decides they’re done. In the next section, we’ll see how we can use the stream’s state to achieve just that.